Dear Clients,

For our first letter of calendar 2018, we decided to write about our experience working with our employee-partners over the years to build Jefferies’ Investment Banking business. While similar stories can be shared about our equally important Equity, Fixed Income, Research and Support efforts, Investment Banking now represents over 50% of Jefferies’ Net Revenues and, by focusing on only one area, we can more easily make some important observations. For background, one of us has been at Jefferies for only 28 years, and the other a mere 18, but over our combined nearly five decades with the Firm, we have had more than our fair shares of twists and turns, ups and downs, and failures and successes. Our goal is not to brag or gloat in any way, and to be clear, we acknowledge we are in the early stages of building every one of our businesses and have a very long way to go to achieve our potential. The point of sharing some of our experiences and observations is to highlight the realities of dedicating oneself to helping build something special that one cares deeply about.

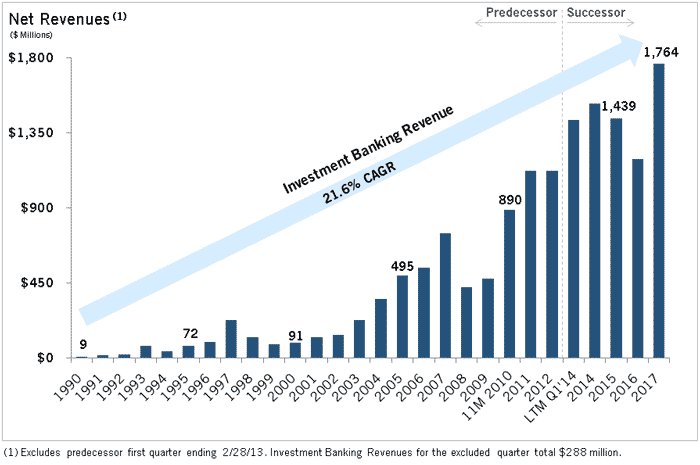

Below is a graphical representation of the past 28 years of Jefferies’ Investment Banking Division:

JEFFERIES INVESTMENT BANKING REVENUES SINCE 1990

It is said that a picture is worth a thousand words, but the reality is that the 28 bars on this graph cannot begin to explain even one percent of the hard work, incredible accomplishments, painful setbacks, and good and bad luck that every one of us at Jefferies has experienced along this journey. The following are some of our thoughts about our experiences, some of which you may want to emulate and some of which you may want to avoid if at all possible as you build your respective businesses:

1. You have to start somewhere. In 1990, Jefferies had one product: riskless trading of cash equities, essentially as a third market agency broker. We had no research, no fixed income, no capital markets, and certainly no investment banking. A small handful of us joined Jefferies with experience in advising and raising capital for companies and we wanted to see if we could do it on the Jefferies platform. The thought was brash and without strategy or forethought. Our team had a total of $30 million of trading capital, with 10% of that seemingly large sum ($3 million) allowed to be in any one industry. That said, we just wanted to try to do a deal. We actually raised $30 million for Buttrey’s Supermarket, in what turned out to be the only LBO done in 1990, as the high yield market was completely blown up following the collapse of Drexel. We got the deal done for our good friends at Freeman Spogli who did what good friends do, took a chance by giving us the opportunity to perform for them at our new firm. The thing we learned from this deal that generated (a then whopping) $900,000 in underwriting fees, 10% of that year’s investment banking revenues, was this: it was more gratifying for us to do this small deal at Jefferies than it was for us to be involved a few months prior at Drexel in the $26 billion buyout of RJR, which was at the time the biggest deal ever done. We learned something from that first small deal: for us, being a partner even in something small is much more rewarding than being an employee of something big. That was the day we decided we wanted to build Jefferies into something truly meaningful. (Talk about coming a long way — in 2017 Jefferies was the number one underwriter of loans for LBO’s on Wall Street according to Bloomberg and we are incredibly proud of our entire team).

2. If you only have a hammer, everything looks like a nail. From 1991 through 1996, we used our expertise to do high yield deals regularly. This was basically because it was all we knew how to do. If a convertible bond walked in the front door, a high yield bond went out the back door. If an M&A deal came in the same front door, a high yield bond went out the same back door. Restructurings, equity deals, whatever the capital need was, a high yield deal was our answer. It is hard to imagine that so-called “unconflicted” M&A boutiques that have sprouted up today don’t suffer from a similar affliction. We learned the hard way that if you want to build a real Wall Street firm or even just an investment banking business, you need a lot of quality people with vastly diverse and complementary skill sets. We realized it was not about what we could do, but rather what was best for our client. This is the core value we have used as the foundation for much that we have built since.

3. Concentration works great until it does not. By 1997, we had hired our first research and equity capital markets teams and decided to invest heavily in a single industry — energy. Oil was around $20 per barrel in 1997 and we had our first breakout year in investment banking, with nearly $200 million in net revenues, primarily as a result of our plethora of energy transactions. It felt really good and smart. In 1998, oil collapsed to $12 per barrel and suddenly we weren’t as smart as we thought. Our revenues dropped by close to 50%, and the infrastructure we had built up to handle all of our deals became a major drag on profitability. It was then that we realized that the only way to build a truly sustainable banking business was to be as diversified as possible by industry, product and geography. This was going to take a lot more money, hard work and patience than any of us had ever thought. If you don’t have all three, it just isn’t going to work.

4. Brands don’t come easy. From the late 90’s to early 2001, we had critical mass in people and had done enough deals to be credible, but our brand was mediocre at best. When you start a new venture in finance, you get business a few ways. First, your friends who know and trust you will give you the benefit of the doubt and, if you perform, you have a business — if you do not, you have fewer friends. As an aside, one of our early friends who gave us a chance was the investment grade company Leucadia, which had every large firm on Wall Street begging for their business. They gave us one deal and we performed, and another and another, and the rest is history. The second way you get business when you are the new guy or gal on the block is to do the toughest deals that the larger competitors don’t want to devote the extra time and energy to figure out. As much hard work as this is, it makes you great at doing tough deals and going the extra mile for your clients. The negative is that it is easy for other competitors to say they “didn’t want to do that deal” when the reality is they just wanted the low hanging fruit. Upstarts can get easily pigeonholed as the firm to do tough deals and that is generally not the place where people want to bring their easier transactions (not that any are truly that easy). We spent a long time doing harder deals and proving to the world we could keep going, and then year by year we broke into a much wider assortment of transaction types. Our client list today is the envy of our competitors and we are very proud of it. By the way, the clients for whom we did the early tough deals became loyal for life and our competitors can’t understand why they cannot penetrate them (e.g., Landry’s and many more). Our brand today has never been better, and is an advantage that we will never take for granted, as we fully recognize how fragile it can become with even one stupid mistake.

5. Critical mass and industry expertise move the needle. From early 2001 to the third quarter of 2007, things went great as we built up our capital base, created a bank loan underwriting capability in partnership with MassMutual and, most importantly, made the bold move to acquire several high quality single sector investment banking boutiques. This gave us teams of quality people who enjoyed working together, had true industry expertise, enjoyed an abundance of special client relationships and were able to leverage the multiple products on our larger platform to best serve their clients. This was truly the beginning of our continual journey to become industry leaders. Eventually, we realized that all the combined names with hyphens and mixed brands from the old boutiques were no longer needed, and we morphed each quasi-independent group into the cornerstone of our various Jefferies industry groups. The bottom line is that each boutique gave us the critical mass to improve our brand and capabilities in its respective industry. It became clear that coming together as one firm was the only way to truly best serve all our clients’ needs.

6. The first rule for building a business is to stay in business. When you are building a business, you have to have no ego, be keenly aware of the challenges of volatile markets, and know where you stand in relative importance to society. Every 3-5 years, the world does appear to turn upside down and the more success you have, the tougher it will be in the downturn — due to overhead, commitments, increased capital, raised expectations and reduced flexibility. Our investment banking revenues dropped by nearly 50% from 2007 to 2008. Our firm had its first (and only—knock on wood) loss in our history. The financial world was on fire and it didn’t matter how big or small you were. We chose to raise equity dollars early (April 2008) to fully plug the hole from our operating loss and contrary to others who all believed their stock price was too cheap so they refused to dilute. Since the purpose of this note is to share our story of building an investment banking division — what credibility would we have if we could not effectively manage our own capital structure in a downturn? Avoiding a margin call and living to fight another day is always the most important rule to follow if you want to build a business. Sometimes it is not about dilution.

7. The best time to play offense is when everyone else is playing defense. If you want to build, the best time to do it is when competitors are disappearing or aggressively shrinking. This means you need to stay humble during the good times and not do anything too stupid — so you can take advantage of the bad times. In bad times, you can hire amazing people who are eager to join on fair terms, and they become long term partners, versus the mercenaries who always have one eye open for the next better short term deal. Our headcount grew by almost 1,000 people from 2008 through 2011 across Jefferies. We added an incredible healthcare banking team, built out our presence in Europe, hired world class professionals across fixed income and made many other strategic moves that forever changed the quality and breadth of Jefferies. The other thing to learn about these periods of time is that one effective way to move up in the rankings quickly is to be fortunate enough to stay in business when many of your competitors do not. Easier said than done.

8. Sometimes it is personal. Unlike in 2008, when our entire industry was under siege, in 2011, we had a well-publicized personal attack on Jefferies from a “misinformed” marginal player in the financial markets who chose a very dangerous time to spread untruths, and the result was an all-out short attack on our company that we don’t wish on our worst enemy. Through the hard work, commitment, and integrity of all our people, we got through it and had a serious question to answer. How could we best continue to build our company given the reality of almost having been destroyed by lies? For that reason and many others, we decided to merge with our now parent company Leucadia in March 2013 in an all-stock transaction that gave us the firm foundation to continue building our business further. Our parent company today has over $10 billion of shareholders’ equity, only $1 billion of long term debt, ample liquidity and an appetite for further smart growth. If the foundation is not strong, it is impossible to build your business.

9. Culture is what counts. Culture is defined in challenging times. Having lived through 2008 and, more importantly, 2011, our firm learned what it truly meant to be independent, entrepreneurial, client focused, flat, honest, not too big to fail, dedicated and appreciative of each other. As soon as we combined Jefferies and Leucadia, we reignited the push to bring in new partners who were complementary, retain our existing partners who brought us to the party, and invest in our people through increased training, communication and time together. The markets were not perfect, but we made progress and saw a path to get to the next level.

10. Be careful what you wish for when you want to get to the next level. We messed up in 2015 into very early 2016, and unfortunately the new level we were striving to hit turned out to be a major drop in investment banking revenues to a level last seen around 2011. Jefferies barely broke even as our balance sheet was too big given the change in the environment and we had too much going on that all correlated. We strayed a little bit too far down the risk spectrum and, as often is the case, when it rains, it pours. The only thing you can do at such a point if you want to get back to building your business is to be ruthlessly honest and transparent, own up to your issues and enlist everyone’s help to try to fix the problems. At the end of the day, the buck stops with the two of us, so finger pointing is useless and solves nothing. Our teams created a bottoms-up plan for the trading side of the firm and we kept keenly focused on recruiting and expanding our investment banking footprint, regardless of how stupid we felt. It is very easy to panic in tough times and “pivot to safety,” but when you stop investing in your core business, your “pivot to safety” may only give yourself a false sense of security. You need to have employee-partners, boards, shareholders, debt holders and rating agencies who are all informed, and you must treat them like partners. If you do, you can still keep building prudently even after you make a mistake. That said, you had better be humble and honest about the mistakes you made and not repeat them.

So where does this leave us? As you can see from the chart above, Jefferies had $1.76 billion of investment banking net revenues in 2017 — the best in our 55 year history (only 28 years really count, we know). Our firm had a record year and our market share, deal quantity and quality, human capital and brand are at all-time highs. The point of this entire note is to tell everyone that our steeply upward sloping diagonal arrow highlighting a 21.6% 28-year CAGR may look wonderful, but the reality is that there were almost as many downs as ups and mistakes as successes. We will continue to have setbacks. We will lose people we want to keep and fail to attract people we want to have join us. We will have investment banking and trading missteps and we will make dumb decisions. The trick in our opinion is that you can and will make many small mistakes, just don’t repeat the same ones. What cannot be allowed is to get the big decisions wrong. The big decisions include your people, culture, capital structure, strategy and brand. It also helps to be incredibly persistent, surround yourself with people smarter than you are and ignore the gossipers and naysayers. Plus, whenever possible, we strongly recommend you throw in a little good luck for good measure.

Happy New Year and we hope to help each of you build your businesses as you help us build ours,

Rich and Brian

RICH HANDLER

CEO, Jefferies Financial Group

1.212.284.2555

[email protected]

@handlerrich X | Instagram

BRIAN FRIEDMAN

President, Jefferies Financial Group

1.212.284.1701

[email protected]

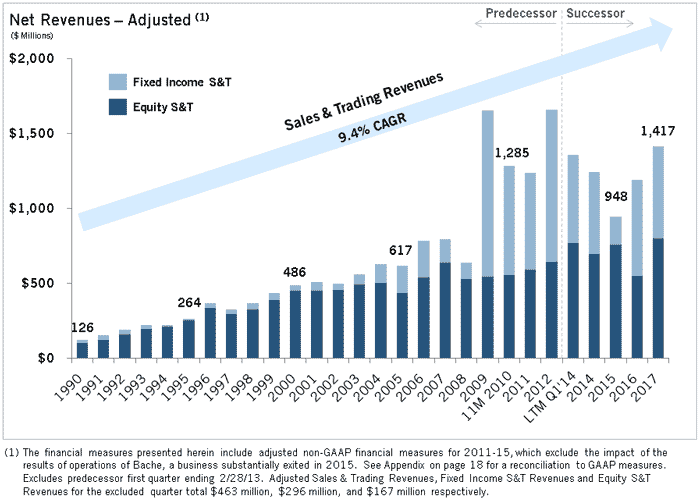

P.S. It is a story for another time, but for those who are curious what the same chart would look like for Jefferies in Equities and Fixed Income trading businesses over the same period, here it is:

JEFFERIES SALES & TRADING REVENUES SINCE 1990

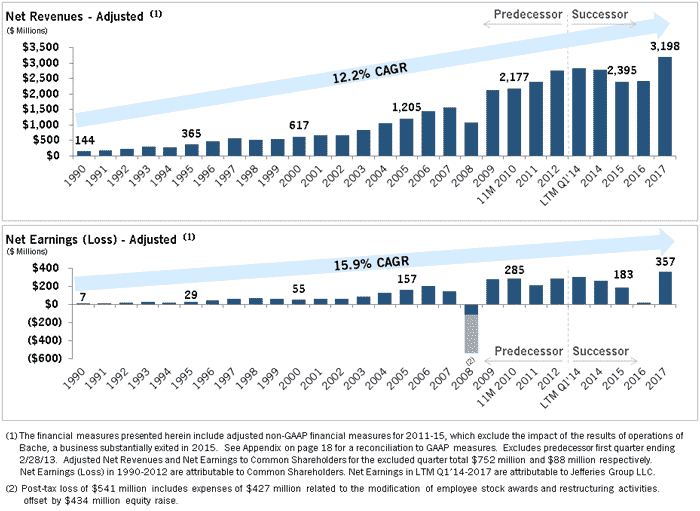

P.S.S. And for the sake of completeness, here is the same chart for all of Jefferies since 1990:

JEFFERIES REVENUES AND EARNINGS SINCE 1990

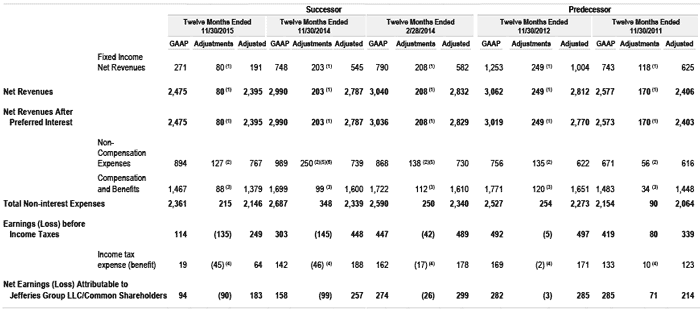

RECONCILIATION OF CONSOLIDATED ADJUSTED FINANCIAL INFORMATION ($ millions)

This presentation of Adjusted financial information is an unaudited non-GAAP financial measure. Adjusted financial information begins with information prepared in accordance with U.S. GAAP and then those results are adjusted to exclude the operations of Jefferies’ Bache business. Management believes that the disclosed Adjusted measures and any adjustments thereto, when presented in conjunction with comparable U.S. GAAP measures are useful to investors as they enable investors to evaluate Jefferies’ results in the context of exiting the Bache business. These measures should not be considered a substitute for, or superior to, measures of financial performance prepared in accordance with U.S. GAAP.

(1) Revenues generated by the Bache business, including commissions, principal transaction revenues and estimated net interest revenue, for the presented period have been classified as a reduction of revenue in the presentation of Adjusted financial information.

(2) Expenses directly related to the operations of the Bache business for the presented periods have been excluded from Adjusted non-compensation expenses. These expenses include floor brokerage and clearing fees, amortization of capitalized software used directly by the Bache business in conducting its business activities, technology and occupancy expenses directly related to conducting Bache business operations and business development and professional services incurred by the Bache business as part of its client sales and trading activities, including estimates of certain support costs dedicated to the Bache business. Estimates of certain support costs were derived based on direct support costs for the presented period in relationship to the average head count of corporate support personnel with responsibilities associated with operating the Bache business.

(3) Compensation expense and benefits, including salaries, benefits, cash bonuses, commissions, annual cash compensation awards and the amortization of certain share-based and cash compensation awards, recognized during the presented period for employees whose sole responsibilities pertained to the activities of the Bache business, including front office personnel and dedicated support personnel, have been classified as a reduction of Compensation and benefits expense in the presentation of Adjusted financial information. In addition, compensation and benefits for other corporate support personnel with duties specific to the Bache operations included in this adjustment were estimated based on an average per person cost applied to the average head count for this employee population type across the presented periods.

(4) Reflects the income tax expense (benefit) associated with excluding the items in net revenues, non-compensation expenses and compensation and benefits expenses associated with the Bache business.

(5) Non-compensation expense includes amortization expense during the presented periods of intangible assets, which arose in connection with the purchase accounting associated with the Leucadia transaction in the second quarter of fiscal 2013, which has been classified as a reduction of Non-compensation expense in the presentation of Adjusted financial information

(6) Non-compensation expense for the purpose of the Adjusted financial information is adjusted for goodwill and intangible asset impairment losses of $59.5 million related to the Bache business.